Where the ice melts

Ragnar surveys Drangajökull’s east side for the second time. He took over from his father, Þröstur, who did it for 25 years. Þröstur took over from his uncle, Guðfinnur, who was in charge of the previous 50 years.

Where the ice melts

Part 1 - Reykjarfjörður

“The first thing I do when I get here is take off my watch and put it in a drawer. We know the approximate time of day by observing the tidal changes. We sleep when we’re tired and we wake up when we’re done sleeping,” says Ragnar Þrastarson. The concept of time seems to have a different meaning in Reykjarfjörður.

Ragnar, his father Þröstur and Erla, Þröstur’s twin sister, came on a small bush plane for their yearly autumn trip to Reykjarfjörður to prepare their houses for winter. Reykjarfjörður, a fjord on the east side of the Drangajökull glacier, was the home of their ancestors for generations. Now, it’s a retreat for their extended family to spend their summers; a way to introduce a quiet way of life to the youngest generation, far away from any roads and modern comforts.

“It’s a wonderful place,” says Erla. “It’s so peaceful to just sit and watch the clouds and the birds.” She points up towards the sky and the ridge beyond, “I start each day by looking out my window towards the glacier, then I check the weather. I never get bored.”

Life wasn’t always this relaxing in Reykjarfjörður. For centuries the bay was populated by people who had to work hard to put food on the table - they hunted, farmed, fished and processed driftwood. Big logs would come into the bay on ocean currents from Siberia, logs that provided the material to build houses and fences on farms around the country. The people of Reykjarfjörður would gather the logs, put them on sleds and have horses pull them over the glacier to the Ísafjarðardjúp region where wood was scarce.

This pool connects us all. It’s the centerpiece of our community

The name, Reykjarfjörður (smoky-fjord), comes from the area’s geothermal qualities. “Jóhannes, our father, was 12 years old when a man came from Reykjavík and taught the kids here to swim in a warm pond. Each spring the adults had to dig and pile up rocks to remake the pond that the glacial river destroyed every winter,” says Erla. After that experience, as a young adult, Jóhannes decided to establish an athletic academy. His vision was to teach skiing on the glacier, running on the beach and swimming in the thermal water. He gathered support from the community and on July 2nd, 1938, they opened a concrete pool in the presence of 73 guests. For over a decade, kids came from all over the region to learn to swim. The program continued until there wasn’t any youth left - the last permanent resident of Reykjarfjörður left in 1964.

The pool is full of 40°C water and open year-round for those few travelers who make the journey. “This pool connects us all. It’s the centerpiece of our community,” says Erla as she emptied the money box containing the entrance fees for the entire summer. “When we are here we sometimes go in three times a day - it’s where we hang out and socialize.”

Ragnar, Þröstur and Erla spend an entire day preparing the houses for the coming winter as they won't return until spring. They close chimneys and cover windows; empty hoses and tie down anything loose. Winters in Reykjarfjörður are brutal and they must be thorough to make sure everything is still there when they come back in spring.

Once the houses are ready, we prepare to exit the region on foot over the glacier so that Ragnar can take his measurements. He needs to conduct the annual ice line survey for the Icelandic Glaciological Society, a community of glacier enthusiasts who push research, host presentations and organise glacier expeditions for their members.

Watch the videos

Part 1 & Part 2

Where the ice melts

Part 2 - Drangajökull

It’s obvious that there have been dramatic changes here lately

This year is Ragnar’s second survey of Drangajökull’s east side. He took over from his father, Þröstur, who did it for 25 years. Þröstur took over from his uncle, Guðfinnur, who was in charge of the previous 50 years. “Lets see if I can do it for 25 years and keep it within the family for a century,” Ragnar says with a spark in his eyes.

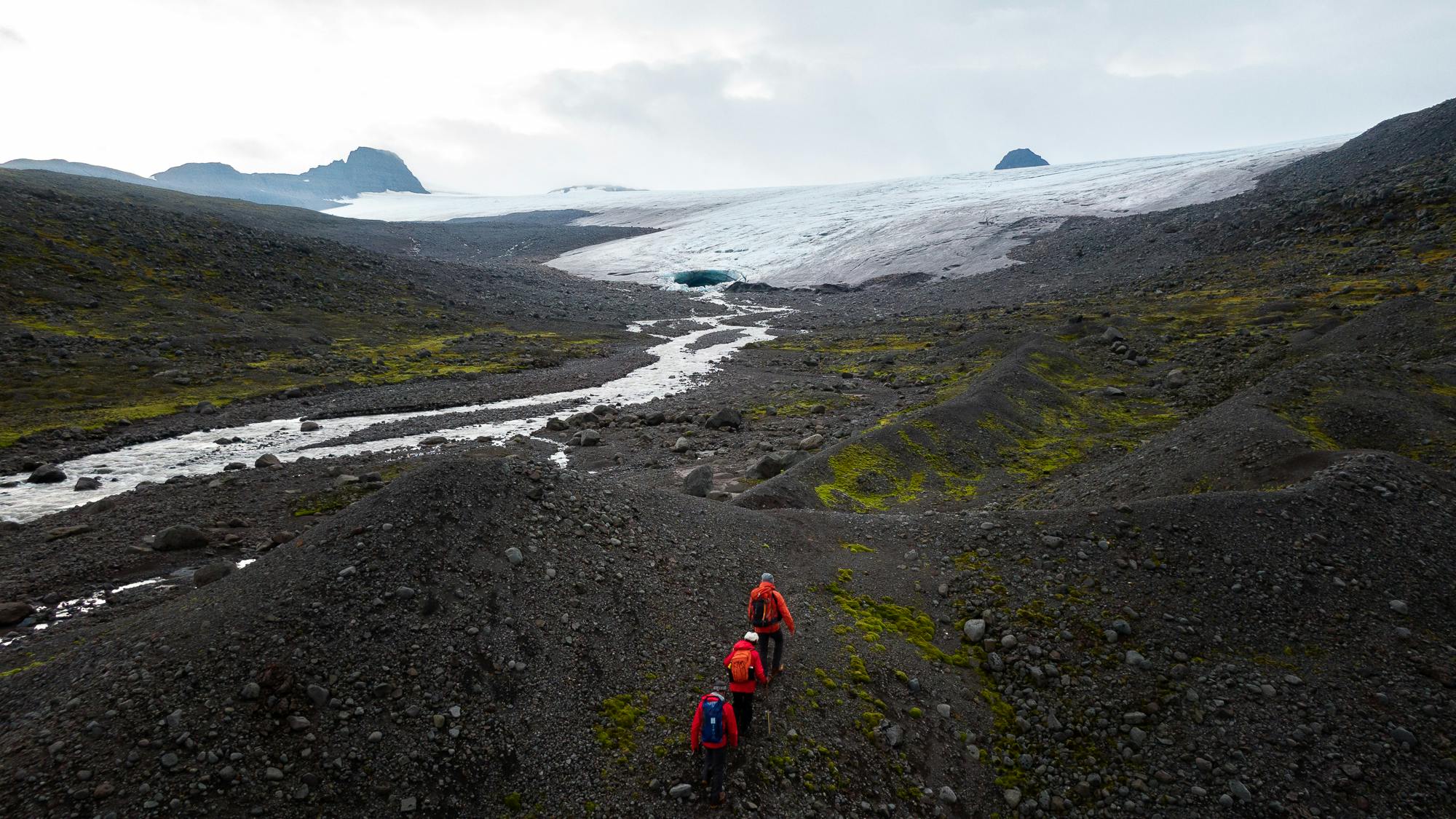

We walk through the soft, autumn landscape on our way to the harsh glacial terrain. Still far from the glacier edge, Þröstur stops by a big boulder and shows us an old copper bar that had been drilled into it. Guðfinnur Jakobsson placed it there to mark the glacier edge when he began measuring the glacier in 1945. From where we are standing, there are still at least two kilometers to walk to reach the edge of the ice today.

We continue along the river towards the ice, where Ragnar takes out his GPS device and finds last year’s ice line. “It’s obvious that there have been dramatic changes here lately,” he notes. The glacier has receded 60 meters in the past 12 months.

For a long time it was a general thought that Drangajökull was Iceland’s only glacier that wasn’t shrinking.

“Well, that’s not quite right anymore,” says Ragnar Þrastarson, geographer at the National Meteorological Office and volunteer for the Icelandic Glaciological Society. “Last year we found that the glacier edge had receded 40 meters from the previous year. This year it’s another 60 meters. It’s the most dramatic change ever measured at Drangajökull since the annual systematic measurements began.”

Amongst Icelandic glaciers, Drangajökull is unique in many ways. It’s the country’s northernmost glacier and the only one in Iceland which lies entirely below an altitude of 1000 meters. Because it’s so far north, it began to shrink later than the glaciers in the south of the country. At this point, however, it’s disappearing at the same speed as those southern glaciers - new reports state that it might completely disappear if nothing is done.

We walk on towards the ice. Ragnar adds more waypoints into his GPS as Þröstur observes from a distance, happy to have passed on the role. Three generations of their family have kept an eye on the glacier, and while it is changing at an alarming rate, one thing that has not changed is the family’s love for the area, which continues to transcend from one generation to the next.

Glacier Friday

NORÐUR Journal

Last May, the band Hipsumhaps released the album Lög síns tíma and January 1st. the album will disappear from all streaming channels and never return.

Glaciers make Iceland an extraordinary place. Let's do what we can to keep it that way.

Together with Ocean Missions and Ása Steinars, we are setting sails towards sustainability.

Follow the NORÐUR Journal with the PÓSTUR or follow us on Instagram